Is your project too human-centric?

A successful product innovation fulfills the “three lenses of innovation”: desirability, viability, and feasibility. If your innovation process emphasizes one of them over the others, it is likely to fail spectacularly.

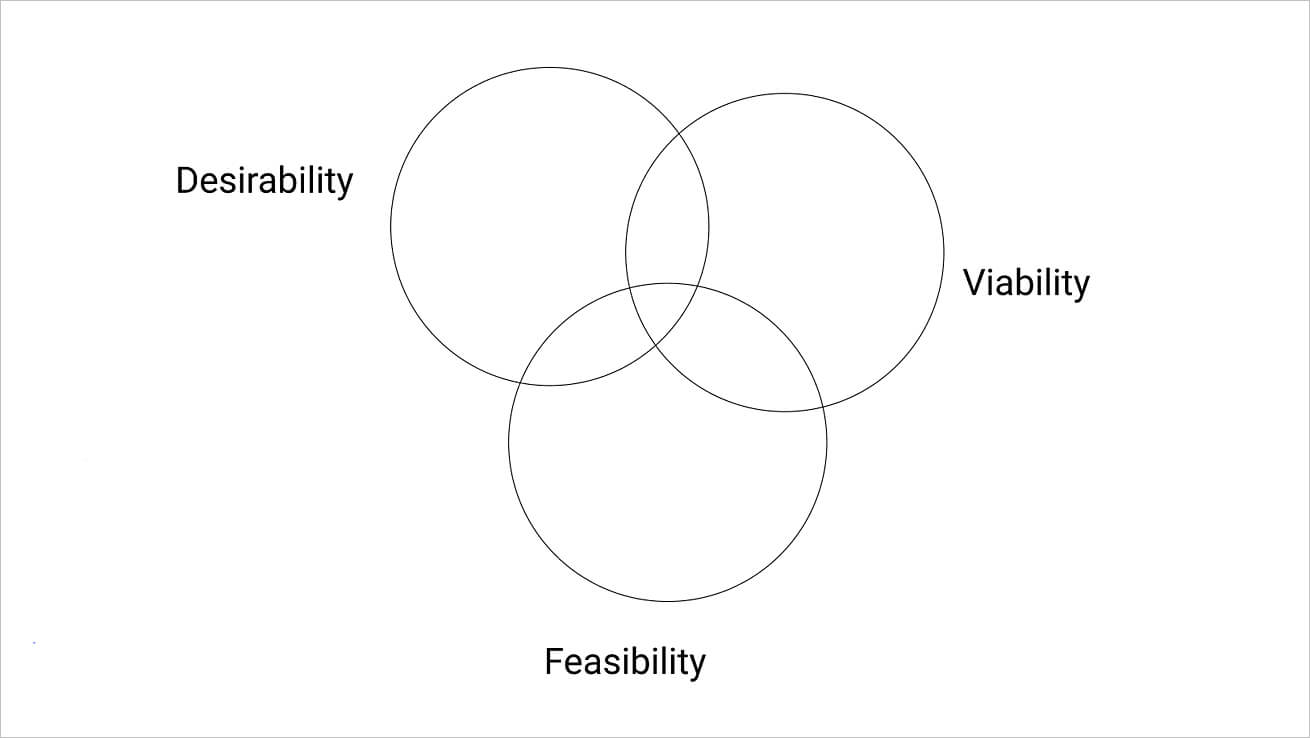

Three lenses of innovation

For an innovation to be successful it must fulfill the three lenses of innovation [1]: desirability, viability, and feasibility.

The proposed solution must be useful and desirable for the end-users, it must be implementable within reasonable costs, and it must provide a business model that ensures that the investment is worth the effort for all the involved parties.

Three lenses of innovation (IDEO)

Three lenses of innovation (IDEO)

Reaching the sweet spot in the intersection of these lenses is by no means an easy endeavor. Many innovation projects fail because the proposed product doesn’t address all three requirements. To avoid this, companies use different innovation process models to maximize the probability of hitting the sweet spot in the intersection of the three lenses.

Human-centric innovation process

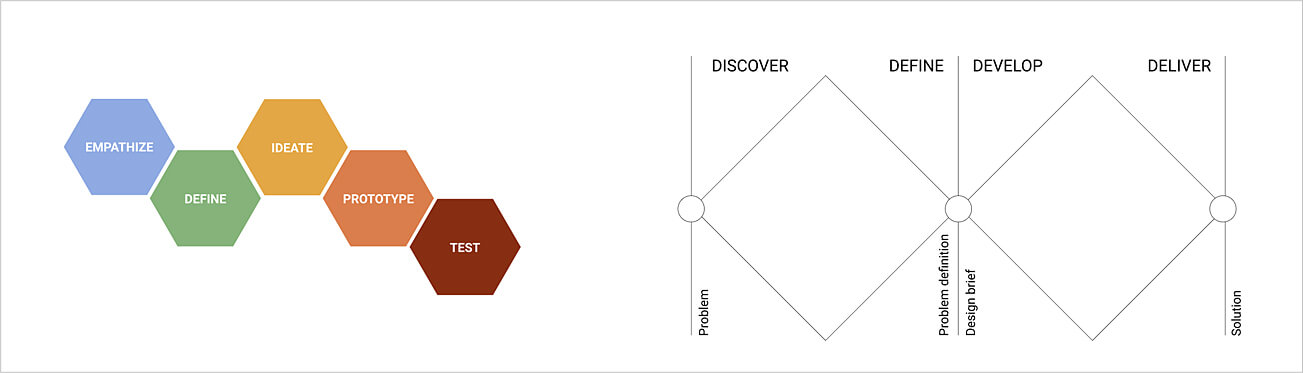

A commonly used model for innovation is the Design Thinking framework, originally from Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (d.School) and later popularized by IDEO. A typical design thinking process [2] consists of five consecutive phases: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test.

Another widely adopted model is the Double Diamond by British Design Council

Design Thinking and Double Diamond process models

Design Thinking and Double Diamond process models

Both of these models aim at finding the sweet spot in the intersection of the three lenses of innovation. However, they tend to be applied in a manner that is biased towards desirability — to fulfill the requirements of the customers and end users of the proposed solutions (note the “Empathize” as the first phase in Design Thinking). This is understandable as these models can be seen as a counter-movement to the engineering-focused product development processes that were prevalent before the emergence of these new human-centric models.

The risk of being too human-centric

In mid-90s the user-centered design movement was relatively new. In my work at Nokia Research Center we applied human-centric design (HCD) rigorously because we expected this to provide the best innovations. This was quite understandable: we had seen purely engineering-driven innovation fail repeatedly when the innovative technical gadgets didn’t gain any traction with the users.

We did qualitative research among the target user groups to understand their needs and underlying motivations. We designed concepts that matched these needs, built prototypes, and finally evaluated the proposals with the target users. This took typically several months. After practicing this design driven innovation process, we became pretty good at it. Most of our concepts resonated very well and were attractive to our potential users.

Yet our innovations failed: our concepts were often difficult or expensive to implement, and we couldn’t demonstrate that they would provide a viable business model. Because of this they didn’t move forward within the organization. At the end, our success rate was not any higher than that of the engineers.

Our process was too human-centric.

Any-centric is not any better

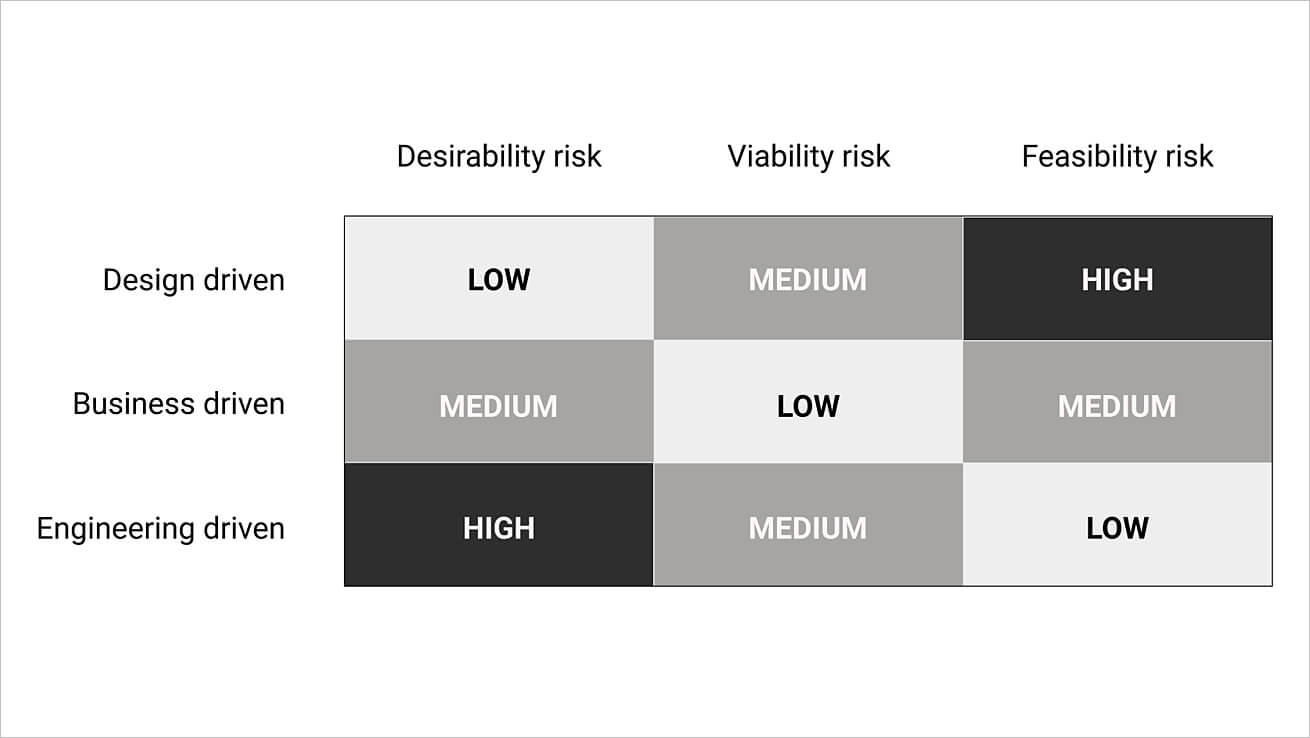

As we experienced at Nokia, you can overdo the human-centricity of your innovation project. As it turns out, if you over-emphasize any one of the three lenses of innovation, you always run a great risk of failure.

An engineering organization approaches innovation by concentrating on the technical brilliance of the solution and ensuring the feasibility of the solution. In my experience, engineers are excellent at solving problems. What they are less attuned to is finding the right problem to solve.

Engineering-led innovation projects run often high risks in the desirability and therefore also a fair risk with the viability: they may estimate the costs for the solution but not the customer value, which is the primary contributor to the income side of the business model equation.

All in all, it seems that if you strongly prioritize one of the three and neglect the two other lenses of innovation in the process, you run a high risk of failure. The following table summarizes the different risk factors when the innovation process is strongly driven by one of the lenses only.

Summary of risks in any-driven innovation projects

Summary of risks in any-driven innovation projects

We should note, that there are some other risks involved that do not naturally land on any of the three lenses that you need to take into account, too. These include risks related to regulation and legislation (“we may not do this”), related to the fit to the organisation’s strategy and brand (“we shouldn’t do this”), the capabilities of the organisation (“we can’t do this”), or related to the sustainability of the solution (“it’s not good for the planet”).

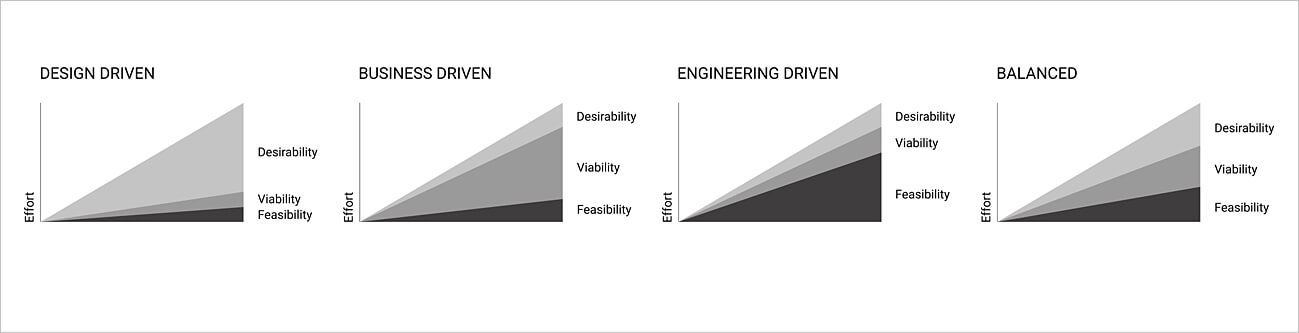

Balance your innovation process

After realizing the risk of any-centricity, it is quite obvious that you must aim at a balance: none of the three lenses should run ahead of the three others.

“Always work on the riskiest assumption first.”

For example, in your purely human-centered design process, you run a risk of facing a major obstacle in the viability and feasibility later. You potentially need to abandon most of the work done so far, take a step back in the process, correct your assumptions and start proceeding again.

In our example, in the mid-90s we didn’t put almost any effort into the viability or feasibility. We were naively assuming that our concepts were implementable and would be interesting business-wise, as long as they were received well by the users. We also were suffering from the phenomenon, that neither the business owners nor the technologists were not committed to the resulting innovations of ours. At worst this meant that our whole effort in human-centered design was wasted.

Key takeaways

Don’t leave any risk behind: if you keep neglecting one or two of the lenses, you accumulate your risk. If a risk that is left behind materializes, all the invested effort in the other lenses is wasted.

You can use existing process models to inform the typical order of tasks. For example, you can apply design thinking process or the Double Diamond model. Note, however, that these models over-emphasize the desirability: keep working in parallel on the viability and feasibility throughout the process.

Make sure that all the different disciplines representing the three lenses are involved throughout the process. This will ensure that each innovation, assumption, and risk are evaluated with the right expertise, and at the same time, you gain the buy-in from the stakeholders that will be essential in the next steps of the innovation process.

As a summary:

+ start the process by observing your assumptions and risks with all three lenses: desirability, viability, feasibility

+ during the work, always identify your biggest risk and work on that first

+ don’t let any risk accumulate; don’t let any of the three lenses be left behind

+ involve experts throughout the process from all three lenses: designers, business analysts, tech architects

+ use agile and lean principles; they fit perfectly to this kind of balanced innovation process

About Xhilarate

Xhilarate is a design and branding agency in Philadelphia that creates visual brand experiences that engage people, excite the senses and inspire our inner awesome. We are the arsenal of innovation. Xhilarate is a design consultancy dedicated to creating innovative brand and interactive experiences with an unyielding passion to create the extraordinary.

For More Information

Russ Napolitano / East Coast

russ@xhilarate.com

215 983 9990